Hyperlocal Hate: Klavern 101

Are public events hosted by hate groups a new trend in Fort Worth, as the city has claimed? "Hyperlocal Hate" is a miniseries of articles intending to answer that question. This is the first installment. Read the introduction to the series.

A hundred years ago, white supremacists had no need to rent city facilities for their events. The Fort Worth Ku Klux Klan owned their own.

First there was the Klan-owned auditorium (or stadium, or maybe pavilion) near Evans and East Terrell Avenues, located on about 28 acres of land then known as Tyler's Lake. It could supposedly accommodate at least 1,600 white supremacists at a time.

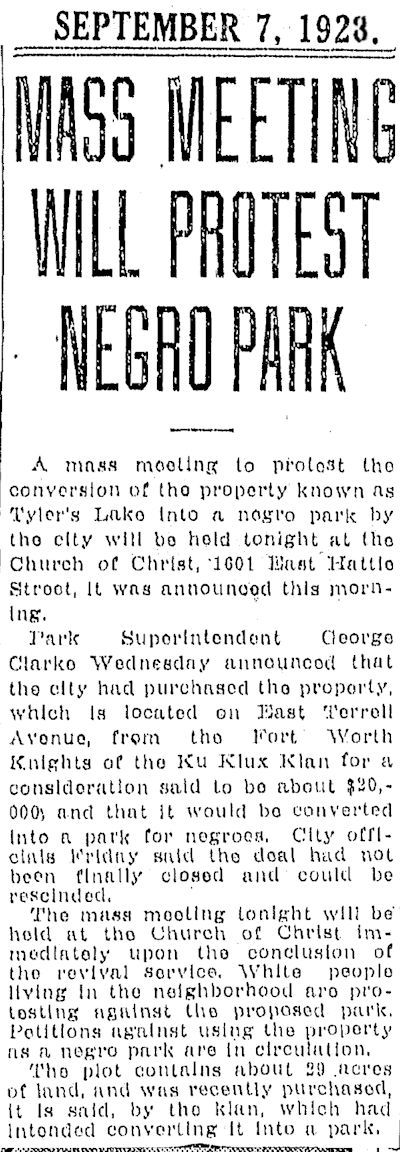

The Klan only owned the Tyler's Lake property for a few months in the summer of 1923. They bought it sometime before June 27, intending to turn it into a "klan park." But by early September, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram reported that the Klan intended to sell the property to the city parks department for $20,000.

The surrounding neighborhood, now known as Terrell Heights, was predominately African-American; the city announced plans to turn the property into a segregated park for Black residents. But even though the local Klan chapter was ready to relocate their program of racial terror, that didn't mean that the white citizens of Fort Worth wanted their Black counterparts to enjoy Tyler's Lake. After weeks of protest by white residents, the city backed out of the deal. (The Klan later unloaded the property for $15,000.)

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, September 5 and 7, 1923.

But Klavern 101 still needed somewhere to host events, so they built a Klan auditorium on North Main Street. Actually, they built two of them. The first, which supposedly seated 4,000, opened in March, 1924. The dedication ceremony featured speakers addressing the tripartite theme: "For God," "For Home," and "For Country." In addition to Klan events and meetings, which were advertised in the newspaper, the hall was rented out to traveling acts. Harry Houdini performed there in October, 1924.

This first Klan hall hosted events for less than a year before being significantly damaged in a fire that November. The fire might have been started by an electrical problem, or it might have been the result of a bombing. The Klan claimed the latter, attempting to frame local African-American community members by producing an anonymous note that claimed responsibility. The note was signed, "The blacks." (Sound familiar?)

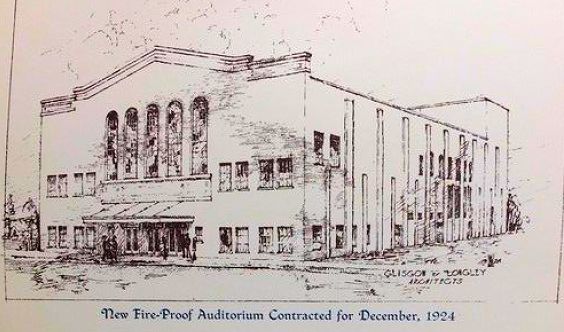

The Klan set about rebuilding their auditorium, fire-proof this time. It reopened in early June, 1925, now with a more elaborate facade and a fly space above the stage, which allowed for lights and scrims to be "flown" in and out by rope. This version probably seated 2,000.

Right: Architect's sketch for the replacement Klan hall. Note the fly space, the tall part of the building, at the back. Left: Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 5, 1925.

The Klan doesn't seem to have held onto this auditorium for long, either. By 1927, it had been sold; in the intervening years, it has been used as a warehouse, a non-Klan auditorium hosting dance competitions and wrestling shows, and then as a facility for the Ellis Pecan Company. At some point, the Klan-laid cornerstone was removed, replaced by local bricks that still appear slightly lighter than the rest of the building's facade. But some speculate that the building still reads "Ku Klux Klan Hall," carved in stone, underneath the Ellis Pecan sign.

Before they took ownership of this series of auditoriums from 1923-1927, the Klan found themselves in circumstances much like far-right organizations that want to host events in Fort Worth do today: their choices were either to rent available spaces or convene gatherings and parades out in public. The pre-auditorium-owning Klan did both.

During the first half of the 1910s, Cowtown residents could watch staged revivals of "The Clansman," and then see its famous film adaptation, Birth of a Nation (D. W. Griffith, 1915), at the Byers Opera House on 7th Street. Enthusiasm for the Klan surged in the wake of Griffith's film, leading Fort Worth's police commissioner to task his assistant police chief with forming the city's very own KKK to lead 1916's Halloween parade.

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, November 26, 1911 (left), November 19, 1915 (center), and October 13, 1916 (right).

The costumed paraders became an actual chapter of the resurgent KKK over the next several years, and that chapter needed physical spaces in which to organize their Christian white supremacist violence and political control. By the early 1920s, Fort Worth Klavern No. 101 did business out of a small office at 209 1/2 Commerce Street; for big events, like the initiation of over 900 new members one night in 1922, they had to drive to empty fields on the outskirts of town. When Reverend Caleb A. Ridley, chaplain of the national Klan, came to Fort Worth in 1921, the klavern rented out the Chamber of Commerce auditorium.

And even after they built their own auditorium on North Main Street, the Klan still cooperated with the city to borrow facilities. During the summer of 1924, they "took over" Lubin camp at Lake Worth from the Fort Worth Welfare Association. Rechristened the Ku Klux Klan Kiddie's Kamp for the month of the rental agreement, it was open to "all poor, worthy white children, regardless of creed, religion, sect or nationality." The Klan had to promise that they would return the facility "in as good, if not better, condition than it was in" when they took it over. One hundred years later, that's still the language used in the city's community center rental policy.

If the timeline of these Klan-owned and -borrowed spaces sounds chaotic, that's because the white supremacist organization did not operate unopposed, not even in Texas, not even in the 1920s. While the Fort Worth Klan was able to hold large events in public, beat Russian-Jewish immigrant Morris Strauss, and lynch Tom Vickery and Fred Rouse under the cover of night, their opponents mobilized anti-Klan organizations like the Citizen's League of Liberty.

Anti-Klan activists of the 1920s countered threatened Klan violence by showing up to political rallies armed. They held their own public events with hundreds of attendees. They badgered public-facing Klan officials for secret membership rolls. They objected to Klan-associated police and Klan-tainted jury pools for local trials; one anti-Klan judge "became so annoyed about Klan influence perverting the legal process that he threatened prosecution for any juror who failed to disclose Klan links" (Fort Worth Between the World Wars by Harold Rich, p. 65). They ran anti-Klan candidates in 1924 to counter the wave of Klan-endorsed politicians voted into office two years earlier—and they won, putting Ma Ferguson in the governor's mansion for the first of two terms.

After the 1924 elections, local officials in Fort Worth set to work ridding city government of Klan members. Klavern 101 responded by burning crosses all over the city, but the new city manager refused to back down.

The Klan didn't disappear overnight. And, historian Linda Gordon argues, by the time they started to fade from view in the 1930s, they had already been enormously successful in turning their ideas into government policy:

The Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 was the most anti-immigration law in American history. It reflected Klan values: It severely limited the number of Italians, Jews, Asians, Greeks, Poles and other Slavs, while some 60 percent of all immigrants came from just Great Britain, Germany and Ireland. The Johnson-Reed Act was the law of the land for 40 years — until Lyndon Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

The work of countering white supremacy continues in Fort Worth, though often in frustrating starts and stops. While the segregated park for African-Americans was never built at Tyler's Lake, locals have been working for over 20 years to help the city redevelop the same area. Some plans, like the Evans Avenue Plaza that celebrates significant moments and figures in Texas African-American history, have come partly to fruition. But others have stagnated.

The hackberry tree where Tom Vickery and Fred Rouse were lynched was cut down on December 14, 1921, at the direction of the woman who owned the property where it stood. Today a historical marker commemorates the spot. Beside it, a sign previews the Mr. Fred Rouse Memorial, which has been designed but not yet built. (Work was slated to begin "in early 2024", but I visited the spot in July, and it has not commenced.)

And while the Ku Klux Klan auditorium still stands on North Main Street, there are plans for it too. It was purchased in 2021 by a group of arts and justice organizations united under the name Transform 1012 N. Main Street. They have an audacious plan to turn the building, which is probably the last surviving purpose-built Klan headquarters in the United States, into the Fred Rouse Center for Arts and Community Healing. Transform 1012 selected an architect and design partners in late 2023. They plan to break ground on the project in 2025—a full one hundred years after the current structure was built to house organized Christian white supremacy in Fort Worth.