Hyperlocal Hate: Paschal High's Legion of Doom

Are public events hosted by hate groups a new trend in Fort Worth, as the city has claimed? "Hyperlocal Hate" is a miniseries of articles intending to answer that question. This is the second installment. Read the introduction and the first installment.

Hate group activity looked different in 1985 than it had sixty years prior, across the nation and in Fort Worth. Gone were the days when the Klan could build an auditorium on N. Main Street. Instead, this was an era of small, secretive paramilitary formations that traded public rallies for clandestine acts of violence. This was the era of The Covenant, the Sword, and the Arm of the Lord, a far-right militia that likely never topped 100 members but nonetheless declared war on the US government. It was the era of The Order, a neo-Nazi group that assassinated Jewish radio host Alan Berg in 1984. It was the era of isolated compounds, paramilitary training camps, pipe bombs, plots to poison the water supply, kill lists, armed standoffs, and vigilante "justice."

And in Fort Worth, it was the era of the Legion of Doom: nine (or more) Paschal High School students who carried out a months-long campaign of neo-Nazi terror against classmates and strangers.

The Legion of Doom began with an attempted queerbashing. In the fall of 1984, future Legion members and their football teammates drove over to a place they called "Fag Park," which the local news reported was Forest Park. They wanted to beat up a gay guy or two; instead they encountered undercover cops and fled.

The group reconfigured after this failed excursion, but it's difficult now to reconstruct when the membership settled into the nine students who would eventually catch charges for their crimes.

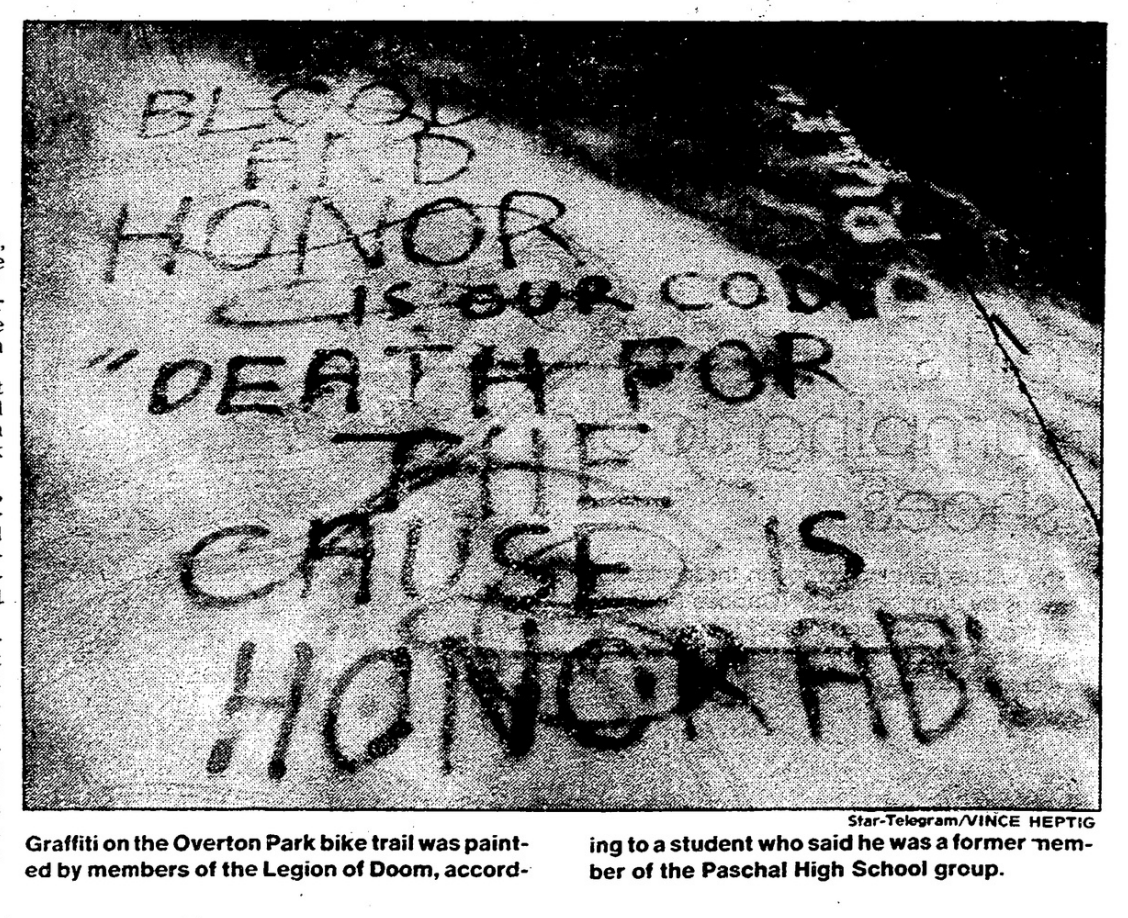

They went back to harassing guys in the park, and took it further, bashing queers like they'd wanted to the first time around. They videotaped themselves yelling slurs at Black and Arab people and using a dummy painted to look like a Black person for target practice. And in case their motivations weren't clear enough, they started covering local parks with anti-semitic and neo-Nazi graffiti: swastikas, slurs, the phrases "aryan lords" and "blood and honor."

Left: the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, March 28, 1985. Right: a still from the tv miniseries Blood and Honor: Youth Under Hitler.

This was not yet the era of the Blood & Honour, a network of British skinhead gangs that came together in 1987. But Blood and Honor had been the title of a TV miniseries about Hitler youth that aired in Fort Worth in November, 1983. Its plot was "constructed around the stories of three families, one upper-middle class, with its social ambitions nicely linked to the rise of the Nazis, another lower-middle class, with nervous reservations about what is happening, and the third Jewish, trapped in the expanding horror of Nazi race laws and theories." The Legion of Doom boys were upper-middle class too.

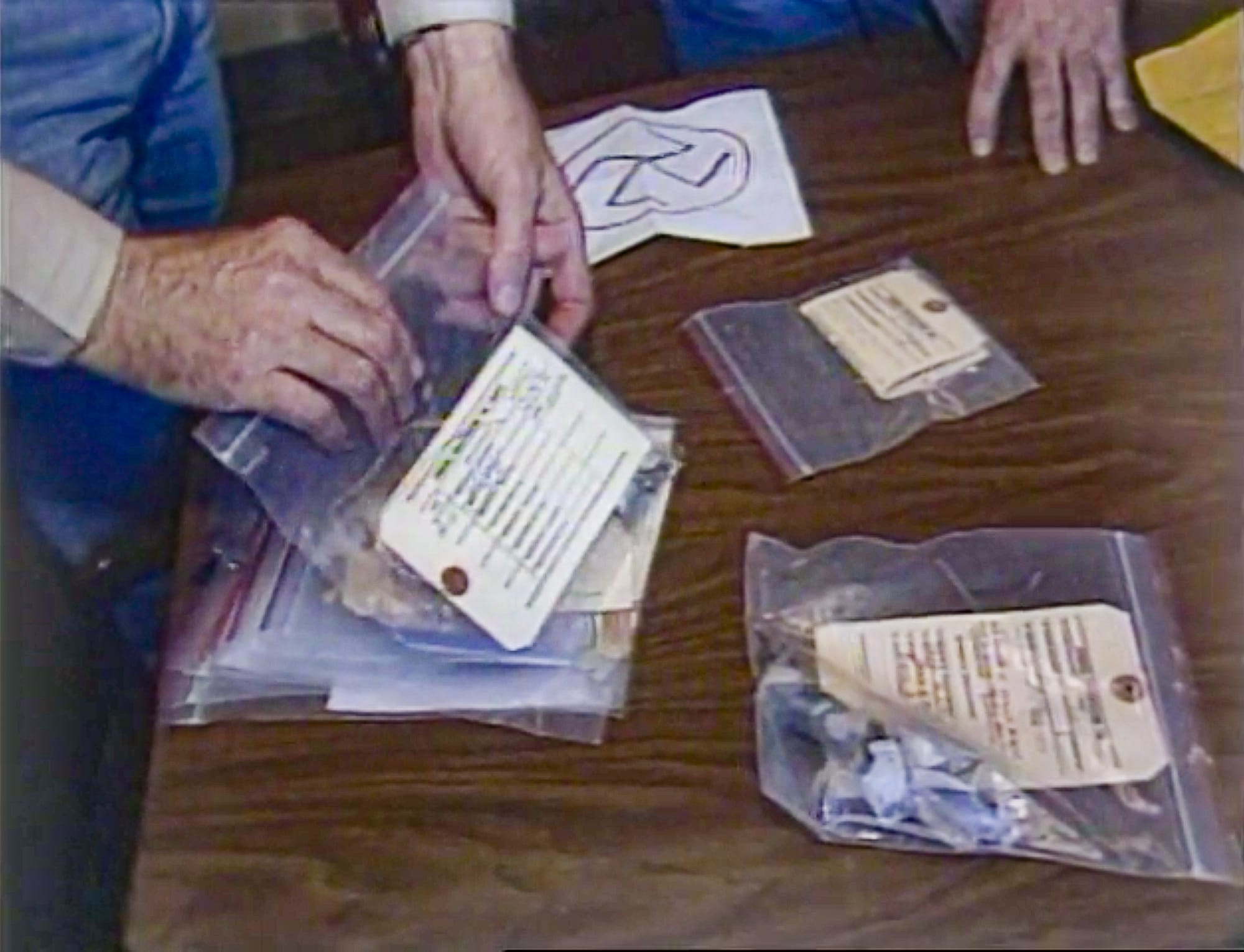

Their social class, their good grades, and their ambitions made it hard for the cops and local news to believe they could be neo-Nazis. In their Top Siders and Izod, they didn't fit the image of skinheads or working-class rural racists. But beyond the swastikas and the notes declaring Paschal High "nazi territory," there were other connections to the era's white power movement. Legion member James Turner read Soldier of Fortune magazine; Charles (Chad) Fillmore had "a thing for Vietnam." Another member claimed a family link to Hitler. They stockpiled weapons and filmed themselves training in military fatigues and burning crosses. They built bombs and a rocket launcher with instructions from The Anarchist Cookbook.

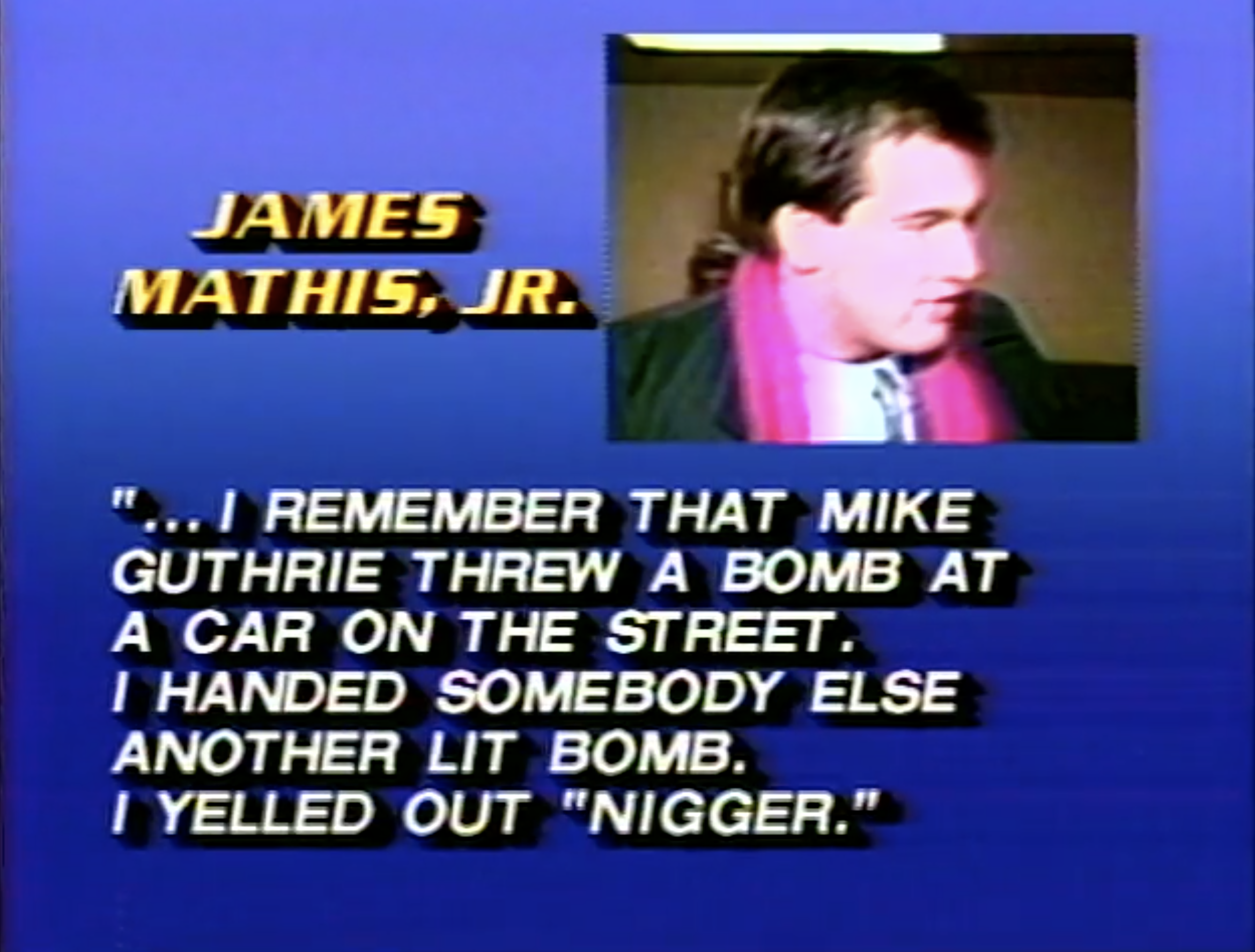

The Legion escalated from weapons training and bomb building to violence in just a few months. By January of 1985, they had tried shooting a Black classmate and his mother through the window of their home, and throwing Molotov cocktails at the home of another Black classmate while screaming the N-word. Neither of these attacks harmed anyone, but the Legion was willing to try—and keep trying.

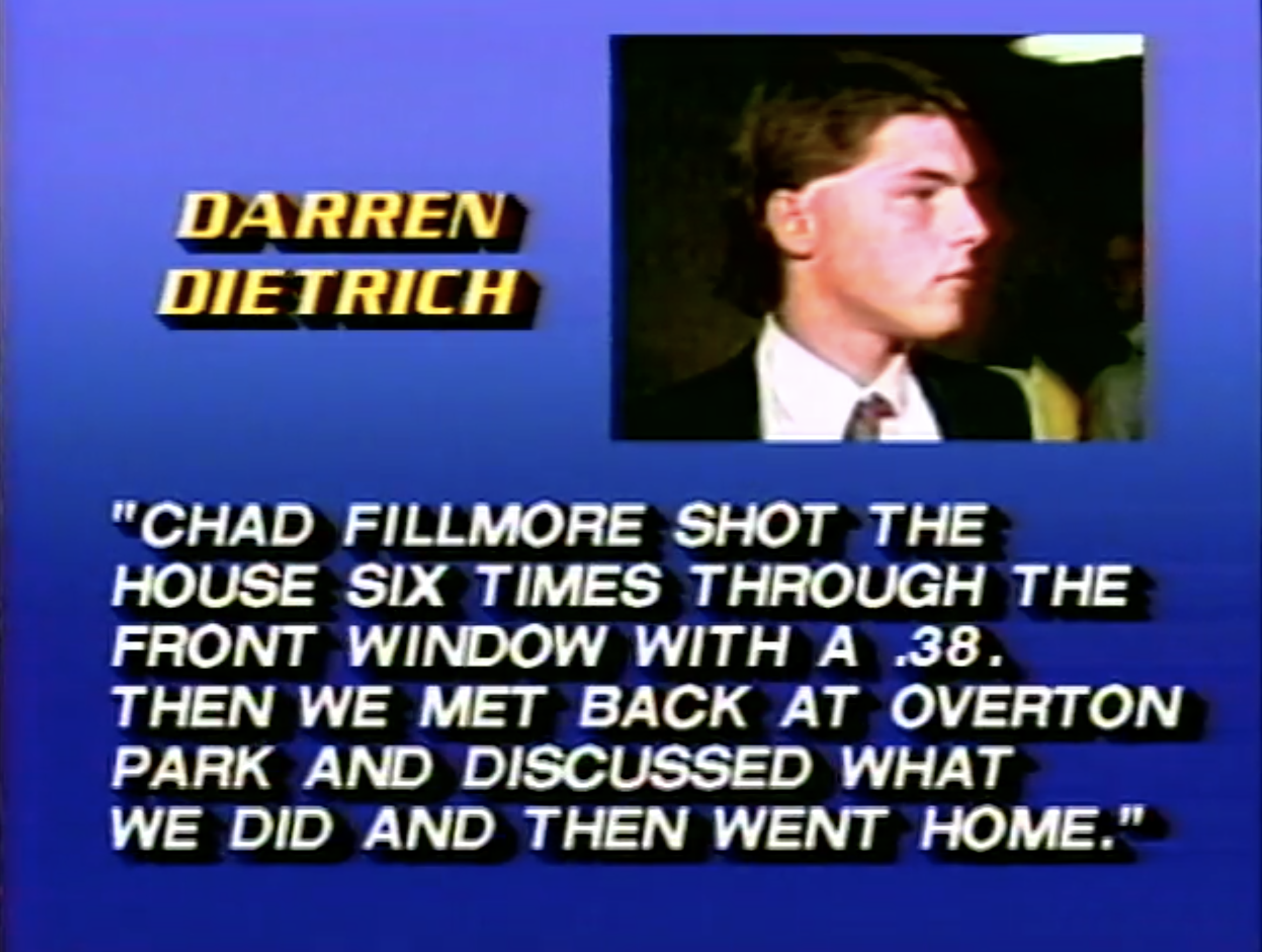

On Friday, March 22, 1985, they shot out the window of a Black former classmate's car. The next night, they shot an arrow at the front door of a white classmate. Then they killed a neighborhood cat, gutted it, and left it inside the car of another white classmate. Then they tried to tape a pipe bomb to the window of a white classmate they'd been harassing since November. The bomb wouldn't stay put, so they set it on the windshield of his car; the shrapnel packed inside damaged multiple nearby cars and houses. Finally, they drove past another classmate's house and shot out his porch light.

And then, presumably, they went home and slept.

Later, after the pipe bomb and gutted cat, Legion members claimed they were seeking justice by targeting drug dealers and thieves at their school. But this was an era of racist codewords trickling down from the presidency into everyday life, and of fear-mongering about the supposed links between minorities, drugs, and crime, all of which the Legion guys were known to parrot. At least one vocally opposed integrating school populations through "busing"—Lee Atwater's infamous code for appealing to racists when you can't say the N-word. David "Beaver" Norman thought people of color lacked "motivation" to better themselves, as he told a local reporter in February, 1985, while he and his fellow Legion members were still anonymously attacking classmates.

They were trying something like the Bernhard Goetz defense, making themselves out to be righteous vigilantes and their victims the criminals. (Ironically, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram ran a story about Goetz's indictment just below the March 28 front page bombshell revealing the Legion of Doom's months of violence. Legion of Doom member Darren Dietrich defended Goetz in a letter to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram published just a week before he and the others were indicted by a grand jury.)

The Goetz defense—an insistence that "fear of crime" justifies violence against people of color—played pretty well in a school district that was still fighting to figure out integration. The Fort Worth Independent School District (FWISD) only made serious progress on integrating after a court order in 1971; in 1983, the district was still refining its integration plan, including revising the geographic boundaries for Paschal High and its various feeder elementary and middle schools. The court system didn't deem FWISD's efforts at school integration sufficient until 1989. That was 35 years after Brown v. Board of Education declared segregated schools unconstitutional.

And so, not even that slowly, the white supremacist aspects of the Legion's reign of terror got dropped from the story. The press stopped mentioning the overt racism and neo-nazi signaling. They called the Legion "vigilantes" instead. They accepted the boys' story about out-of-control crime at Paschal High School, and while they interviewed several students about the Legion, the press never actually investigated whether theft or drug use was a serious problem on campus.

Law enforcement claimed they never could confirm a link between the boys and other white power groups. But this makes the Legion of Doom a quintessential part of the era's white power movement: a successful example of the "leaderless resistance" model called for by neo-Nazi Louis Beam in 1983. Even without orders issued from an external authority, the Legion operated in ideological sync with the broader movement.

And other white supremacist groups took notice, using the Legion of Doom as an example of their own goals and successes. A message posted to the Aryan Nations Liberty Net—the first white supremacist message board, which went online in 1984—praised the Legion by name. Former Ku Klux Klan grand wizard Tommy Rollins credited the Klan's local efforts at recruiting young people in the late 1970s and early 1980s for the Legion's creation. And somehow, newsletters from a Fort Worth white power group ended up in the front yard of the Legion's intended pipe bomb victim.

But none of this white supremacist ideology ended up as part of the legal proceedings against the Legion of Doom. In May, 1985, a grand jury returned 33 indictments for eight of the nine known members of the Legion; none of the charges alleged organized crime or conspiracy, nor civil rights violations.

Legion of Doom members James Mathis Jr. and Darren Dietrich in their own words. From a local news broadcast in 1985.

Seven pleaded guilty to their charges, while another was referred to juvenile court. The judge gave five members of the Legion of Doom short sentences, which were cut even shorter by overcrowding in the Tarrant County Jail. In the end, all five spent no more than two weeks in jail. And because all seven were placed on deferred adjudication, they could avoid having permanent felony convictions on their records, as long as they completed their probations, which were supposed to range from five to ten years.

By 1988, three of the seven had been released from probation early and had their records expunged: Michael Guthrie's probation was cut from five years to two, while Chad Fillmore and David Norman both served only two of their 10-year probationary terms. At the time, the others were expected to apply for early dismissal as well.

Some of the former Legion guys still live in the Metroplex, and if you bring up their story these days, other people are quick to defend them and the violence they did. A Reddit post from 2013 characterized killing the cat as the only thing they did that was "just this side of evil," a spatially and ethically confusing way to describe the acts described above.

The former Legion of Doom members don't appear to have done much of anything newsworthy since the late 1980s. In my research, I haven't come across any evidence that would suggest they remain involved in the white power movement. Although some community members at the time pointed out that their race and class privilege likely protected them from harsher punishment, those lenient sentences may have prevented them from becoming further radicalized towards hate in prison.

In the end, the Legion of Doom story reminds us that, while it takes more than the criminal punishment system to effectively interrupt violent ideologies like white power, this doesn't mean that we should let neo-Nazis operate in secret. It's necessary to expose their activity in order to shut it down—and this remains as true today as it was in 1985.